The Horse That Built the City, and the Car That Rewired It

What the fastest technological displacement in American history teaches us about what’s coming next

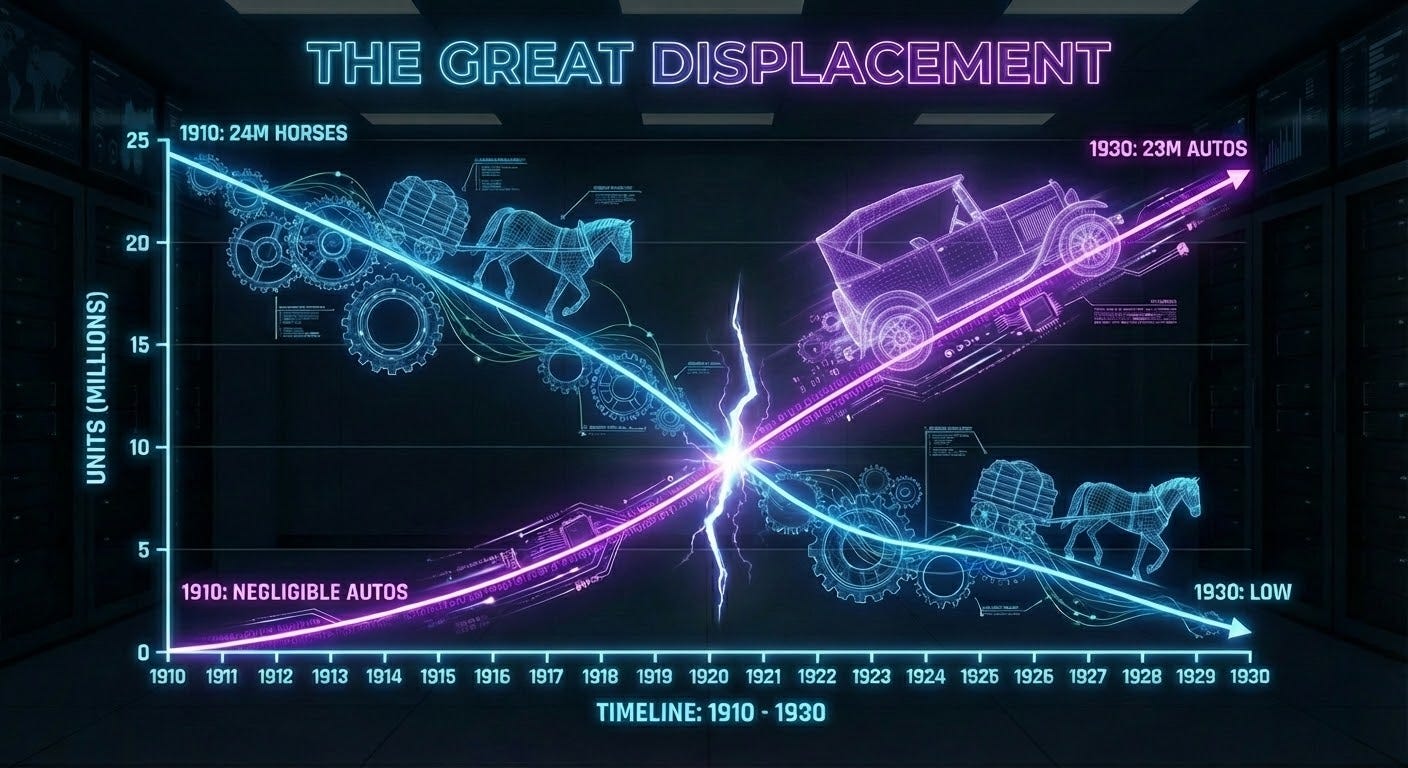

In 1910, America stabled approximately 24 million horses and mules. By 1930, we had registered 23 million automobiles. In a single generation, the animal that had powered human civilization for five thousand years was replaced by a machine that had existed for barely two decades.

I keep thinking about that swap. Not because I’m nostalgic for horses. Because I’m watching the same pattern unfold right now, and most people don’t see it.

The Friction Before the Flip

We sanitize history. We forget how bad it was.

In 1900, New York City maintained approximately 128,000 horses. Each horse produced 20 to 30 pounds of manure per day. Do the math. That’s nearly two million pounds of waste hitting the streets daily in a single city. Add urine. Add the carcasses of horses that collapsed and died in the streets, sometimes left for days because removal was expensive. Add the flies, the disease, the smell that permeated everything.

The “Great Horse Manure Crisis” wasn’t a joke. Urban planners in the 1890s genuinely projected that cities would become uninhabitable. One famously dire prediction suggested that by 1950, London would be buried under nine feet of manure.

They weren’t wrong about the trajectory. They were wrong about the solution.

The solution wasn’t better manure management. It wasn’t more efficient horse breeding. It wasn’t urban horse limits or zoning laws. The solution was a machine that made the horse irrelevant.

How Fast It Flipped

The speed still staggers me.

Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908 at $850. By 1913, the assembly line dropped production time from 12 hours per vehicle to 93 minutes. By 1925, you could buy a Model T for $260. Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $4,500 today. A new technology went from luxury to commodity in 17 years.

New York City’s horse population dropped from 128,000 to 56,000 in a single decade. By 1912, automobiles outnumbered horses on Manhattan’s streets. The infrastructure of an entire civilization, optimized over millennia for animal power, was rewired in less time than it takes to pay off a mortgage.

The national numbers tell the same story. In 1900, there were 8,000 registered automobiles in America. By 1910, there were 458,000. By 1920, 8 million. By 1930, 23 million. That’s not linear growth. That’s an exponential curve that policy, infrastructure, and social norms struggled to comprehend, let alone contain.

The Displacement Sequence

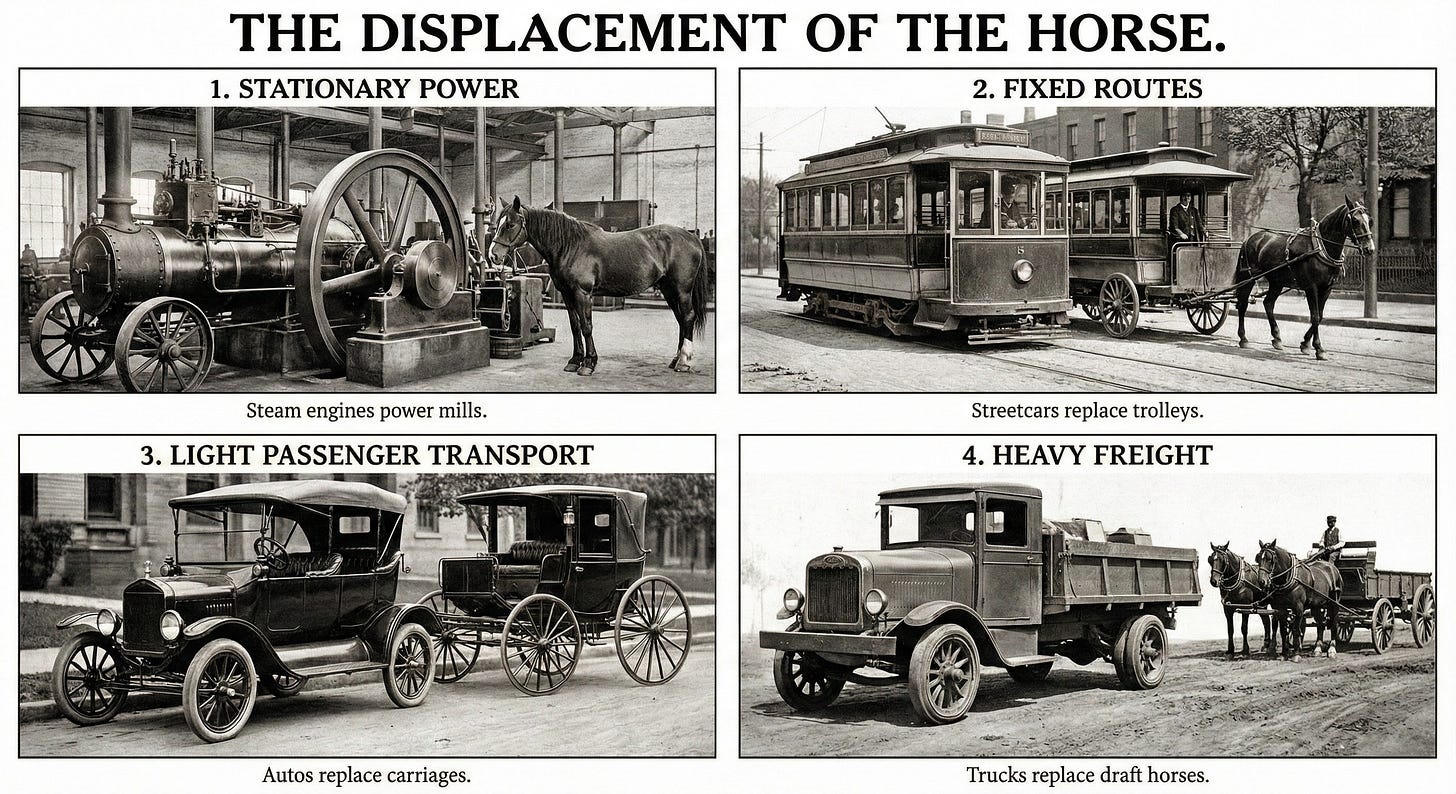

Here’s what I find most instructive: the horse didn’t disappear all at once. It was displaced function by function, in a predictable sequence.

Historian Clay McShane documented the pattern:

First, stationary power. Steam engines and electric motors replaced horses driving mills, pumps, and factory equipment. The horse lost the jobs that didn’t require mobility.

Second, fixed routes. Electric streetcars replaced horse-drawn trolleys. The horse lost the jobs with predictable paths.

Third, light passenger transport. Automobiles replaced carriages and cabs. The horse lost the jobs serving individuals and small groups.

Fourth, heavy freight. Trucks replaced draft horses and wagon teams. The horse lost the jobs moving goods at scale.

The pattern matters because it maps to every major technological displacement. The machine takes the repetitive work first, then the structured work, then the flexible work, and finally the heavy work. Each stage feels like the end of the transition. Each stage is just the setup for the next.

The AI Parallel

I’ve spent the last year building with AI tools. A hundred projects. A thousand hours. I’ve watched the same sequence begin to unfold.

Stationary power (templates and tooling). AI handles code completion, document formatting, data transformation. The repetitive tasks that don’t require context.

Fixed routes (platforms and systems). AI embeds in CRMs, ERPs, marketing automation. The structured workflows with predictable inputs and outputs.

Light passenger (content and support). AI drafts emails, writes first versions, handles customer service tickets, summarizes research. The tasks serving individuals with manageable complexity.

Heavy freight (core workflows). This is where we are now. AI is entering analytics, financial planning, campaign operations, strategic research. The work that moves the business.

The sequence is the same. The timeline is compressed.

What took the automobile 30 years to accomplish, AI will likely accomplish in 10. Maybe less. The Model T needed roads, gas stations, repair shops, and trained mechanics. AI needs only an internet connection and a subscription.

The Horses That Remain

Here’s the part most people miss when they analogize technology transitions: horses didn’t disappear. There are still approximately 7 million horses in America today.

But they’re not doing what they did in 1910. They’re not pulling plows or hauling freight or powering streetcars. They’re doing the things machines can’t do as well, or the things humans prefer them to do for reasons beyond efficiency.

Show horses. Therapy horses. Ranch work in terrain that vehicles can’t navigate. Racing. Recreation. The horse became a premium experience, not a commodity utility.

This is the “boutique future” of any displaced function. When the machine takes the commodity work, the remaining human work becomes scarce. Scarcity creates value. The people still doing it aren’t doing it because machines can’t. They’re doing it because the work requires judgment, taste, trust, or presence that humans still prefer to get from other humans.

In AI terms, I see certain roles gaining premium precisely because they become rare:

Founder-strategy. The ability to see around corners, to synthesize pattern and intuition into direction. AI can inform this but not replace it.

Taste-making. Knowing what’s good, what resonates, what will matter. AI can generate options but can’t yet feel the difference.

Trust brokerage. The relationships where someone’s word is their bond. The handshake that closes a deal. The reference that opens a door.

Novel research. Genuine discovery at the frontier, not synthesis of existing knowledge.

Field leadership. Being present, making decisions in ambiguous situations, rallying humans toward coordinated action.

These aren’t safe because AI can’t touch them. They’re safe because humans will still want humans doing them, even when AI gets good enough. Just like we still want horses, even though cars are faster.

The Operating Playbook

So what do you do with this?

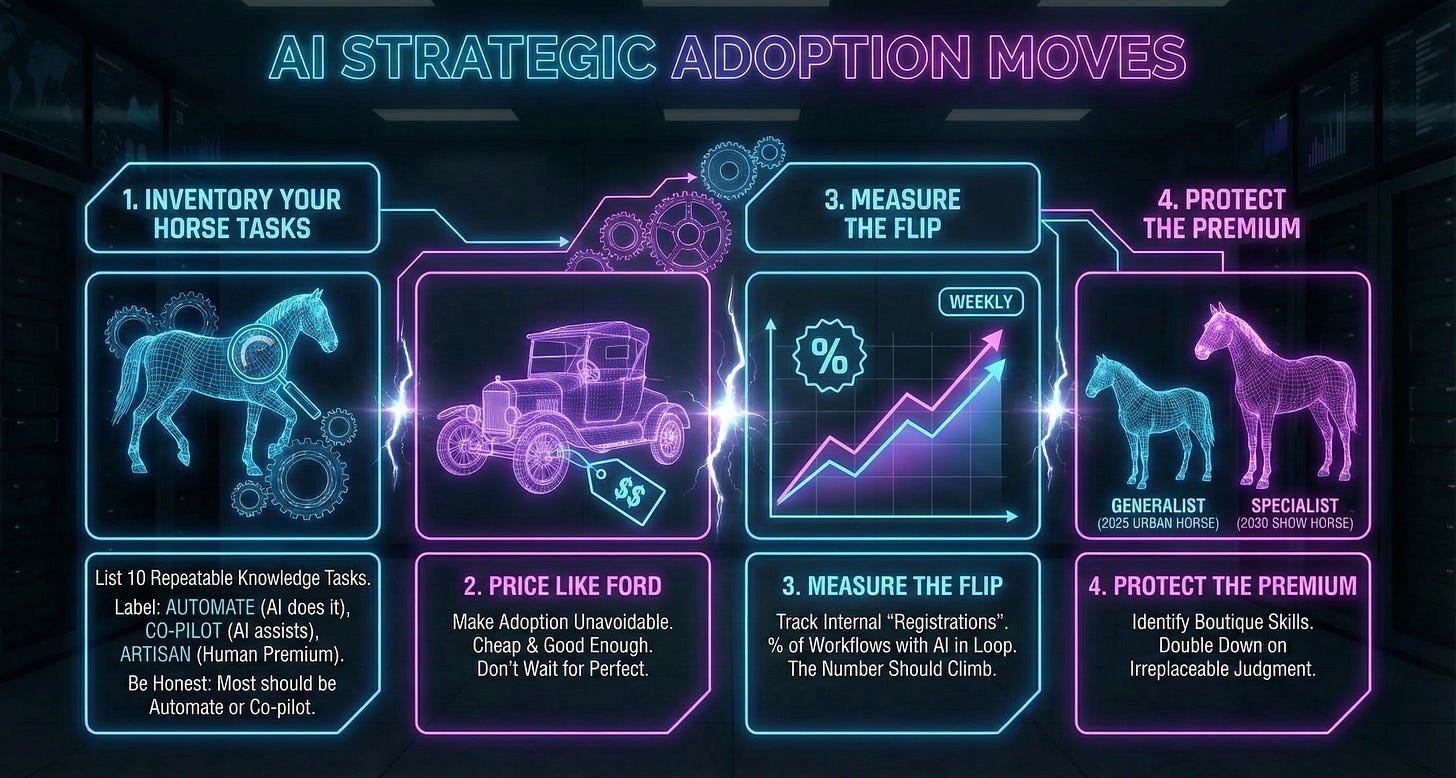

Inventory your horse tasks. List ten repeatable knowledge tasks in your work. Label each one: automate (AI does it), co-pilot (AI assists), or artisan (human premium). Be honest. Most of your list should be in the first two categories.

Price like Ford. The Model T won because it was cheap enough to be inevitable. Find the AI move, the feature set plus distribution, that makes adoption unavoidable for your team. Don’t wait for perfect. Wait for cheap and good enough.

Measure the flip. Track an internal “registrations” metric: what percentage of your workflows have AI in the loop? Measure it weekly. The number should be climbing. If it’s not, you’re falling behind a curve that doesn’t forgive delay.

Protect the premium. Identify which of your skills are heading toward boutique status. Double down on those. The generalist knowledge worker is the urban horse of 2025. The specialist with irreplaceable judgment is the show horse of 2030.

The Question Underneath

Here’s what I keep asking myself: Where in my own work are the “urban horse” tasks? The things that feel necessary today but are fragile under cheaper, faster alternatives?

I’ve found more than I expected. And I’ve started replacing them. Not because I enjoy it. Because I watched what happened to the horse, and I’d rather be the one driving the car than the one still shoveling manure when the streets go quiet.

The cities didn’t bury under manure. They rewired around a new technology. The pessimists were right about the problem. They were wrong about the solution.

The same will be true for us.

The question isn’t whether AI will displace knowledge work. The question is which work, in what sequence, and how fast you’ll adapt when your function comes up in the rotation.

Let’s make it great.

Sources

U.S. Census and USDA historical counts: approximately 24 million horses and mules (1910)

Federal Highway Administration motor vehicle registration data (1900-1930)

McShane & Tarr, “The Horse in the City” (function-by-function displacement sequence)

NYC Municipal Archives: horse population decline 128,000 to 56,000 (1910s)

Model T production and pricing history (Ford Motor Company records)

American Equestrian: contemporary U.S. horse population approximately 7 million