Nine Inches to Infinity

What Moore’s Law Can’t Measure

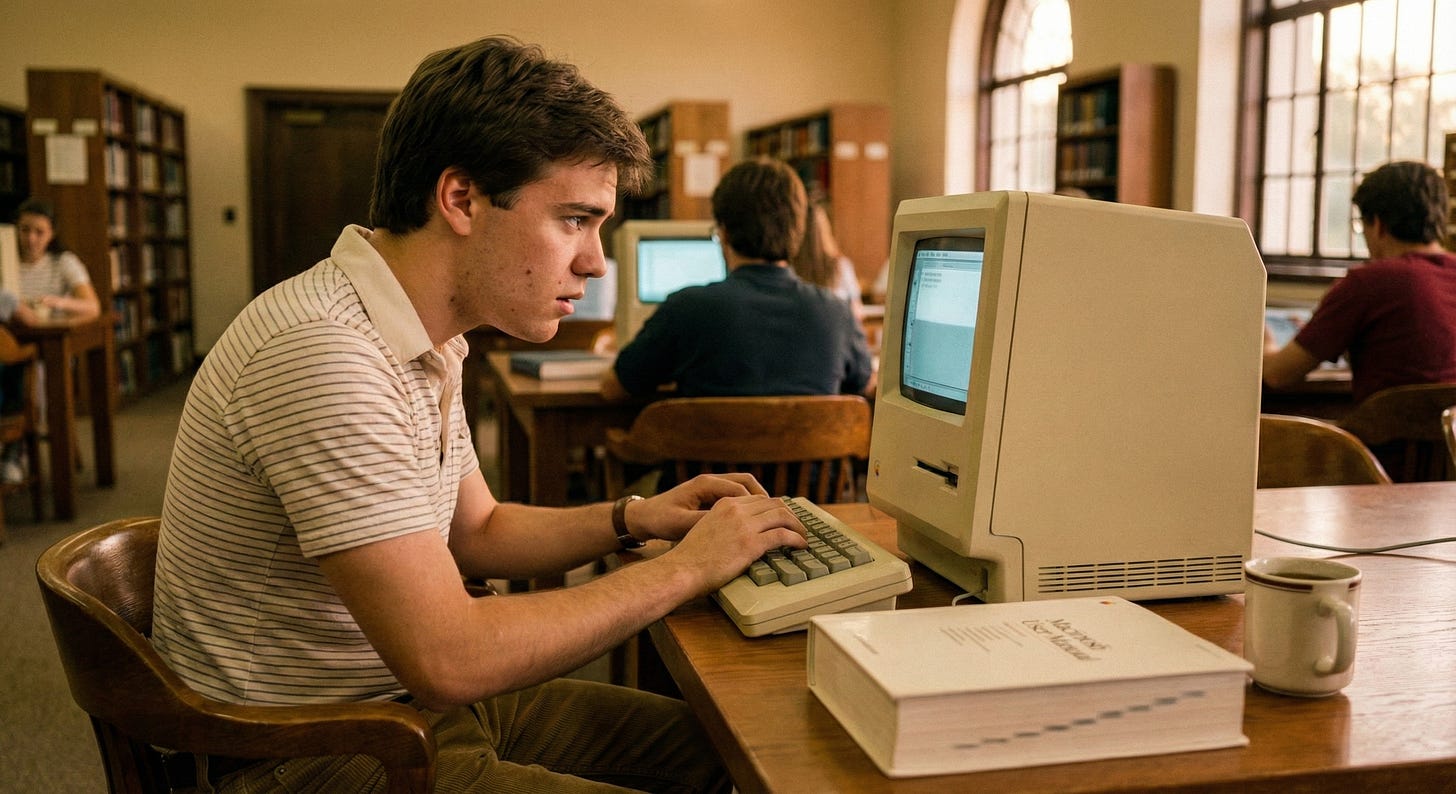

The first time I touched a Macintosh, I didn’t know where to put my hands.

Not because I feared the machine. Because I feared being seen. Being exposed as someone who didn’t belong on the frontier.

It was 1984 or early 1985. The library at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. I was a freshman, and there were juniors and sophomores moving through the graphical interface like they’d been born there. Clicking, dragging, ejecting floppy disks with casual confidence. I didn’t even know how to manage the disk. The beige box sat there humming, its 9-inch monochrome screen waiting, and I felt the particular anxiety of standing at the edge of something I didn’t yet understand but knew I needed.

What I couldn’t have known then: that moment of uncertainty would extend into a 42-year relationship that has shaped everything about how I think, build, and see the future.

The irony is that my father already owned a Macintosh. He’d bought the original 128K model for his real estate and financial consulting business, paired with a dot matrix printer that screamed like a dying robot every time it produced a document. My father was born in 1941. He never touched an IBM PC. His first computer was the Macintosh, financed through a local reseller. At 18, I hadn’t really paid attention. But looking back, it’s remarkable. A man in his early forties, no prior computing experience, intuiting that this particular machine was different. That it was worth the leap.

He was right. So was my gut, standing nervous in that library. We were both, in our different ways, stepping onto the frontier.

Here’s what I was working with in 1984:

A Motorola 68000 processor running at 8 MHz. 128 kilobytes of RAM. A 9-inch screen displaying 512 by 342 pixels, black and white. Storage lived on 400-kilobyte floppy disks that you swapped constantly because the machine could only hold one at a time. No network. No internet. Every bit of information was local, physical, and precious.

To put it in terms anyone can grasp: the entire machine held about 64 pages of typed text in memory. Each floppy disk stored roughly what a single smartphone photo contains today. The screen had fewer pixels than a modern Instagram thumbnail.

And I was mesmerized.

Not by the specifications. By what the machine made possible. MacPaint let me push pixels around with a mouse. MacWrite made words appear on screen exactly as they’d print. This was magic to someone raised on typewriters and Wite-Out. The constraints were severe, but constraints have a way of focusing the mind. Every kilobyte mattered. Every action was intentional.

I didn’t just use the Macintosh. I learned its language. I learned to think in its terms.

Now jump cut to this morning.

January 2026. I’m sitting in front of a 57.5-inch Samsung Odyssey curved display. The resolution is 7,680 by 2,160 pixels. Roughly 16.5 million pixels, compared to 175,000 in 1984. The screen wraps around my peripheral vision like wearing a headset, but it’s 32 inches from my face and I can still drink my coffee.

The machine driving this display is a Mac Studio with an M4 Max chip. 36 gigabytes of unified memory. That’s 281,250 times more RAM than the original Macintosh. I could fit the entire contents of 90,000 of those 400-kilobyte floppy disks in memory simultaneously. The computer connects to the internet through AT&T fiber delivering 980 megabits per second, which is roughly infinity compared to the zero connectivity of 1984.

If the original Mac’s memory was a studio apartment, my current machine is a small city. The screen displays more visual information than your eyes can actually process at once. The internet connection downloads an entire movie in about 30 seconds. What took all night in 1984 now happens before you finish a sip of coffee.

While I’m recording this transcript into a microphone, three Claude Code agents are running simultaneously in separate terminal windows. One is building a web application. Another is refactoring a codebase. A third is surveying my file structure, organizing my desktop, making decisions about where documents should live. I bounce between all of them, checking progress, giving direction, moving to the next.

This is Tuesday. This is normal.

Now here’s where most essays like this would pivot to Moore’s Law. The exponential curve. The hockey stick graph showing computational power doubling every 18 months for four decades. Yes, all of that is true. The numbers are staggering. 281,250 times more memory. Roughly 95 times more pixels. Processing power that makes the 1984 Mac look like an abacus.

If the original Mac’s memory was a single sheet of paper, my current setup is a stack taller than a 50-story building.

But that’s not the story.

The story is what happened to the human in the chair.

Moore’s Law tracked the silicon. Nothing tracked the wetware.

My Mac got 281,250 times more memory. My brain? Same 86 billion neurons it had in 1984. Same two hands. Same retinas that can only focus on one thing at a time. The biological hardware didn’t scale. It couldn’t.

And yet something transformed.

Not my neurons. My relationship to the machine.

In 1984, I served the computer. I swapped disks. I waited. I watched progress bars. I learned the machine’s language because it certainly wasn’t going to learn mine. Every interaction required me to translate my intentions into terms the computer could understand. Human adapts to machine.

Somewhere in the past four decades, that relationship inverted.

I didn’t notice it happening. There was no single tipping point. I progressed through corded mice with rubber balls to roller balls to optical sensors. Through 300-dpi laser printers that felt like science fiction. Through Aldus PageMaker and the desktop publishing revolution. Through Sony CRT monitors at 1024 pixels wide, which I genuinely believed was the maximum size screens could ever reach. Through the first 13-inch color display, which made everything I’d done before feel like cave paintings.

Each evolution felt significant in the moment and invisible in retrospect. The progression from word processor to page layout tool to multimedia workstation to connected device happened so gradually that I absorbed each shift without marking it.

But if I had to name the tipping point, it would be today.

Right now, as I speak these words, Claude Code has complete control of my file management system. I told an AI agent to survey my desktop, make decisions about organization, and execute those decisions without checking with me. The machine isn’t waiting for my instructions. It’s interpreting my intent and acting on it.

I went from operator to conductor. From playing an instrument to directing an orchestra.

This is the transformation that Moore’s Law can’t measure. The shift from learning the machine’s language to training machines to learn mine.

In 1984, I was a soloist. One human, one computer, one floppy disk at a time. Every output required my direct input. The machine amplified my capabilities, but only within the narrow band of what I could explicitly instruct it to do.

In 2026, I’m running a studio. Multiple AI agents working in parallel on different projects. The machine doesn’t just amplify my capabilities. It extends my agency. It makes decisions in my absence. It handles complexity I couldn’t manage alone.

This isn’t just a change in tools. It’s a change in what it means to be a builder.

Sometimes people ask if I miss anything about the early days. The wonder. The frontier feeling. The nervous excitement of standing in that UNCW library, not knowing what I was about to become.

The honest answer is that the wonder never left. It just changed shape.

What mesmerized me in 1984 wasn’t the nine inches or the 128 kilobytes. It was the sense that I was standing at the beginning of something enormous. That this machine represented a doorway to a future I couldn’t yet imagine but desperately wanted to enter.

I still feel that. Maybe more intensely than ever.

The difference is that now I understand the pattern. I’ve lived through enough cycles to recognize when a new one is starting. The Macintosh in 1984. The web browser in 1995. The smartphone in 2007. Large language models in 2023. Each wave felt like the future arriving ahead of schedule. Each one rewired how I work, think, and create.

The Lost in Space episodes I watched obsessively as a six-year-old planted a seed. Will Robinson talking to a robot. Humans and machines in partnership. It seemed like fantasy then. It’s Tuesday now.

Here’s what I’ve learned across 42 years of this apprenticeship:

The machine will always outscale you. That’s not a threat. That’s a feature. Your job isn’t to compete with the silicon. It’s to remain the one who decides what the silicon should do.

The constraints that feel limiting are actually gifts. 128 kilobytes taught me to be intentional. Floppy disks taught me to organize. Slow processors taught me to plan before executing. Abundance is wonderful, but scarcity builds skill.

Staying on the frontier requires continuous transformation. I’m not the same builder who sat nervous in that library. I’ve had to become someone new every few years to match what the machines made possible. That process doesn’t end. If anything, it accelerates.

And most importantly: the tools exist to unlock mental capacity, not replace it. I am still a dreamer and a builder. I have always been one. The compute just got better at keeping up with the vision.

The next 42 years will demand more of this, faster. The curves are steepening. The cycles are shortening. What took a decade in the 1990s now takes 18 months.

The question isn’t whether you can keep up with the machine. The machine will always outrun you.

The question is whether you’re willing to keep becoming. To stand at the frontier again and again, nervous and uncertain and absolutely alive with possibility. To maintain the relationship across every transformation.

My father made that choice in his forties, financing a Macintosh he didn’t know how to use because he sensed it mattered.

I made it as a nervous freshman, stepping toward a beige box that terrified me.

I’m making it today, handing file management to an AI agent while I speak into a microphone.

Same dreamer. Same builder. 281,250 times more memory.

The tools change. What matters doesn’t.

This essay was drafted in conversation with Claude, continuing a 42-year tradition of building alongside machines.